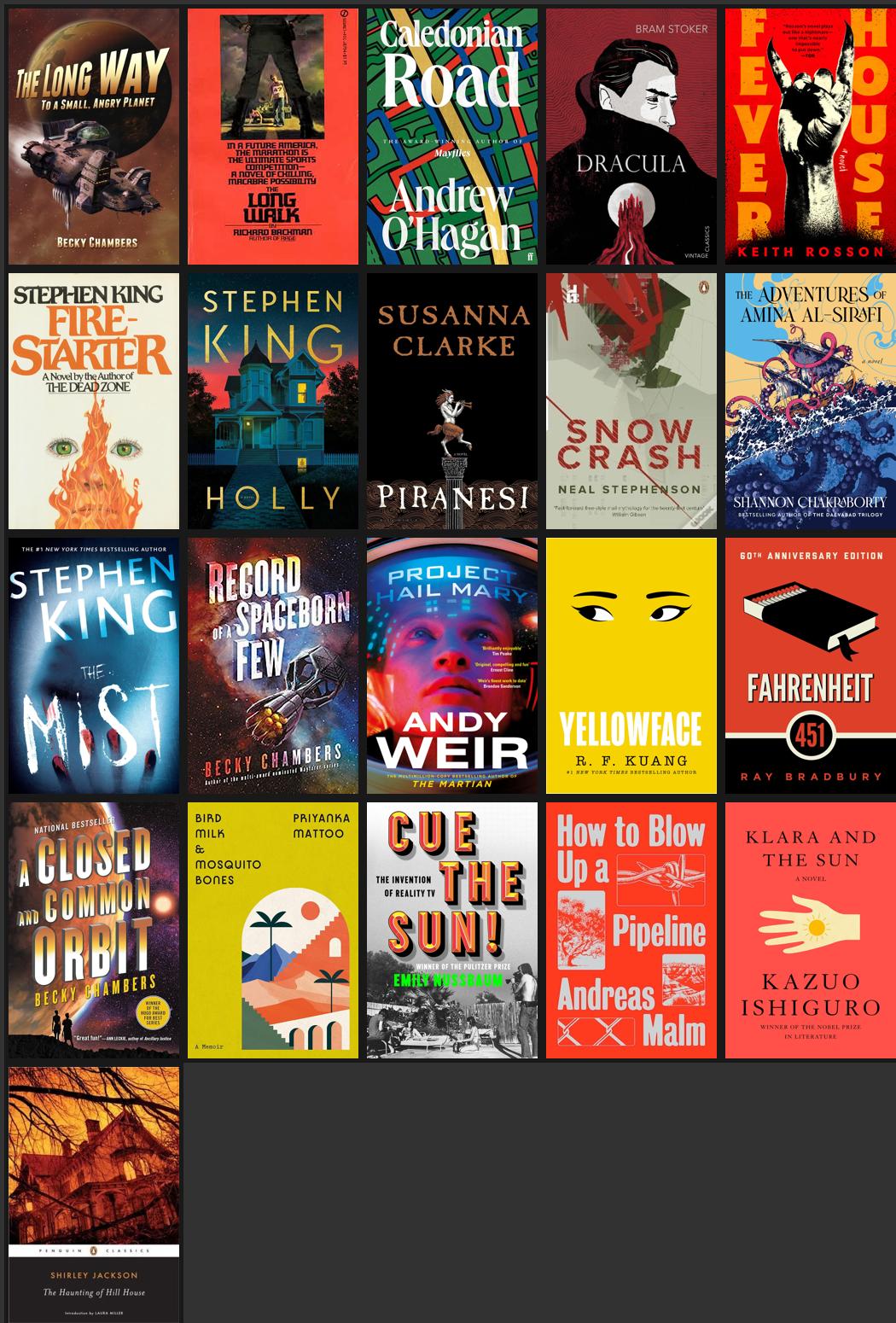

2024 Book Recommendation List

Please note: These are my thoughts on the books at the time that I read them and wrote about it. My opinions change with time, with experience, etc. These are not gospel on what I think of a book - they are snapshots of a particular time.

The list

The image is not ordered by any particular rating system. I will, however, share with you what I rated each book as. First, a quick explanation of my rating system - I use a 5-star rating system, where the different scores mean the following:

-

5 stars: these are the books that have not only taught me something, but that I feel like I will remember in ten years. I would wholeheartedly recommend books in this category to anyone who asks. If I had to build a library with the different books I’ve read over the years, the 5-star category of every year is what would populate it.

-

4 stars: these are books that I thoroughly enjoyed reading and that I thought were above average, but that don’t quite make the cut of five-stardom. For instance, an otherwise excellent book with an unsatisfying ending would fit here; or an excellent, rompy ride where I think the prose isn’t anything to write home about. I would still recommend books in this tier to people most of the time, but I would consider them less essential reading.

-

3 stars: these are the books that I thought were pretty okay. There’s nothing particularly wrong with them, and most of them do more than a couple of things right, but when it comes down to it they’re not books I think I will remember for a long time. To think of them as the airport reads of this list might be a bit too harsh of a description, but the mind wanders in that direction. Think of the books in this section as perfectly okay, but with nothing that made me want to rave about them.

-

2 stars: these are books that I don’t regret reading, but would not read again and don’t particularly recommend. They usually have more than one trait that bothered me and, overall, took some degree of forcing myself to continue reading in order to finish them. That isn’t necessarily to say the books are awful or not worth reading - just that I did not enjoy them for one reason or another (I will do my best to expand on why).

-

1 star: these are books that I had no fun reading, learned nothing from, and regret spending time with. It’s relatively rare for books to land themselves in this category, and I try to find redeeming qualities in most of the things I read, but sometimes I just think books are genuinely dreadful.

The books, ordered by rating

Here are the books in the above list ordered by their rating, descending:

-

5 stars:

-

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, by Becky Chambers

-

Record of a Spaceborn Few, by Becky Chambers

-

Fahrenheit 451, by Ray Bradbury

-

-

4 stars:

-

A Closed and Common Orbit, by Becky Chambers

-

Bird Milk and Mosquito Bones, by Priyanka Mattoo

-

Cue the Sun, by Emily Nussbaum

-

How to Blow Up a Pipeline, by Andreas Malm

-

Klara and the Sun, by Kazuo Ishiguro

-

The Haunting of Hill House, by Shirley Jackson

-

The Long Walk, by Stephen King

-

-

3 stars:

-

Caledonian Road, by Andrew O’Hagan

-

Dracula, by Bram Stoker

-

Fever House, by Keith Rosson

-

Firestarter, by Stephen King

-

Holly, by Stephen King

-

Piranesi, by Susannah Clarke

-

Snow Crash, by Neil Stephenson

-

The Adventures of Amina Al-Sirafi, by Shannon Chakraborty

-

The Mist, by Stephen King

-

-

2 stars:

- Project Hail Mary, by Andy Weir

-

1 star:

- Yellowface, by R.F. Kuang

Commentary on the books, by descending order of rating

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, by Becky Chambers

Last year, I read A Psalm for the Wild Built and did not particularly resonate with it. I thought it was a cozy, interesting book, but ultimately felt pretty non engaging to read, and I wasn’t the target audience for it. But Becky Chambers is too beloved by her fans to ignore, and I decided I would give her another shot with The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet.

Boy, am I glad I did.

Much like in A Psalm for the Wild Built, the characterization here is great; but, instead of being applied to just two main characters, here it’s extended to a sprawling cast of interesting aliens. And while the book is still character driven, there is now an actual plot to give the characters a sense of purpose, turning this into more of a story than the voyeuristic experience of Chambers’s other book.

When I say interesting aliens, I mean interesting aliens. The Wayfarers’ universe contains some of the more interesting depictions of non-human races I’ve seen in a while, each refreshing in its originality and deep in its characterization, cultural considerations, and unique ways of reacting to the same stimuli. Ohan, the navigator from a race that sacrifices their sense of self to a parasitic entity in the name of superior reasoning skills, all the while making that parasitic entity the subject of religious worship, is a particular highlight; as is the absolutely excellent Doctor Chef, a rumbling cook that embodies all that is good about good food. And while I single these out for their particular staying power in my mind, I loved them all - this ragtag crew of interesting folks fulfilled the same sort of space opera cravings that I’d had all the way since Firefly. It is much lower stakes, but it also shares all the qualities of something like Mass Effect, and does not shy away from serious subjects when the story warrants that care. It had me seriously touched by the end of the book, and handled delicate things that are hard to write well about - like grief, coming of age, and family - with the gentle touch of some of the most skilled writers I know. Here is where the full package of Becky Chambers’s skill comes together like it hadn’t before for me, and I found myself craving more of this group of misfits when I still was halfway through the book.

I’ll be reading the rest of the Wayfarers series as soon as possible, and I recommend you do too.

Record of a Spaceborn Few, by Becky Chambers

Remember when I said I would be reading the rest of the Wayfarers series as soon as possible? I wasn’t joking. I ended up reading the first three books in the series this year, and while you’ll see the second book further down this list, Record of a Spaceborn Few, the third book in the series, is equally delicious; but for different reasons.

First of all, it’s important to mention that this is not a return to the crew we met on the first book. Instead, with each of the books in the Wayfarers, we get a glimpse into a different part of the universe, while the general overarching plot slowly evolves around the lived experiences of different main characters. This was disappointing to me at first, especially because I liked the crew of the Wayfarer so much that I wanted to continue experiencing their stories. But I once again decided to give Becky Chambers a chance, and once again was rewarded for it.

This time, the book focuses on the Exodus Fleet - the group of humans that ran from Earth once the planet was made inhabitable by previous generations, then drifted across space for decades until they were found and helped by the Galactic Commons species. And much like the previous books, it is not just a strong concept executed competently that drives this book forward, but a strong concept executed with a level of gentleness and care for the lived experiences of people, real people, that are in that situation, that makes this excel. The book is not about what happens to the Exodus fleet - it is about who they are, and it manages that characterization with an attention to detail that is nothing short of best in class.

Many times in science fiction, especially in hard sci-fi, I find myself bracing as the breakneck speed and scale of the stories swirls around me. Space is overwhelming - stories set in space tend to be as well, especially after a little bit. But this is such a contemplative work that it feels like it could be a story about a small village in rural somewhere, what matters to them, and what makes them who they are. The only difference is, it’s about a whole species without a home, clinging to their history and pride as they integrate into a galactic community of far more powerful species, deal with the guilt of destroying their own planet, and strive to find a workable identity to move them forward.

How cool is that?

Fahrenheit 451, by Ray Bradbury

Fahrenheit 451 is part of popular culture by now, as is, generally speaking, Ray Bradbury, so I won’t waste too long on the introduction.

This book resonates with me now, as it did once in the past, because of how much I believe in the power of stories, and in the danger that hides in interacting with them in the wrong way. It was a pleasure to burn, says the firefighter that serves as the main character to the book, the legendary Guy Montag, in a world where being a firefighter is fighting books with fire. Written in 1953, and reeling from imagery such as the Nazi book burnings and the worst of the red scare, Bradbury writes a poignant book with beautiful prose about how much one loses when one does not read, and how much one can regain by restarting; how it is worth risking one’s life for the right to engage with text that touches and challenges us, because to do otherwise is to live numb.

A trite point, you might say, driven home a million times in a thousand different prose styles by other writers. And Fahrenheit is at times hard to read, in the vein of 1984 and similar books where the moral and political charge eclipses both characters and plot; it is a book about something to the detriment of everything else. The prose is at its best when talking about abstract concepts: Beatty’s monologue about the nature of the firemen, for example, is a strong highlight. It is at its worst in simple character interactions: for instance, when Guy Montag is interacting with his wife, Mildred, the dialogue reads like a conversation from a Don DeLillo novel, jilted and full of frustrating non-starters.

But even if you are in the camp of those who dislike the style of prose, Bradbury’s dreamlike writing in a world without the anchor of a shared, story-informed culture is worth reading about. The point it is trying to make is never too trite a point to make again, especially at a time when book banning continues to be a real problem in much of the world, when the poignancy of text and its very soul are under threat by heartless AI slop, and when it has never been more important to protect the value of our literature from the legions of technocrats who can’t draw a straight line from it to value for shareholders. Soulful art does not just show us the boundaries of what is possible; it defines it. And Fahrenheit, with its cautionary tale about the dangers of forgetting this, is worth paying attention to.

A Closed and Common Orbit, by Becky Chambers

Three books in one list? Who is this, Stephen King?

I mentioned I had enjoyed the Wayfarers series so much that I read the first three books this year. A Closed and Common Orbit is the second book of the series, and while it did not make my five star list, it’s still a thoroughly enjoyable book.

It is hard to keep my review here spoiler free, but I will do my best. We follow Sidra, a newborn AI walking the world in a robotic body, as she comes to terms with the notion of her own identity and who she wants to be. This is a particularly interesting conundrum for an AI (an actually sentient one, not a chat bot using the power of an entire small village to steal someone’s copyrighted material), in the sense that it has unlimited access to information, but must exist in a world that does not recognize her as a sentient being, with desires and agency of her own. Does she resign to being human in the human sense, and adopt our culture? Is her desire for self actualization even inherently human, or is it applicable to every living organism? How does the constant interaction with vastly different alien species inform her sense of self? Candid, raw descriptions of very human sensations (like Tak’s descriptions of what it means to tattoo oneself, and why people do it) carry this book with a tenderness and perspective that reach new heights when seen through the eyes of someone who is learning what it means to be someone.

It’s an interesting premise, and handled with the care and mastery that Becky Chambers exhibits in her other books. I did not particularly resonate with Sidra, not nearly in the same way as I had with the crew of the Wayfarer or some of the people in the Exodus fleet, but that is more to do with me than with her.

Why, then, is this in the four star group?

Well, because this book does something I find annoying enough to dock it a whole star, regardless of how strong the rest of the work was. I call this something “Game of Thrones syndrome”, in honor of it happening constantly in A Song of Ice and Fire. Here’s the issue:

The book makes constant use of perspective chapters, told from the limited perspective of the character who the chapter belongs to. This, in itself, is fine. The issue is that it then frequently ends chapters on the highest point of tension, forcing me to read a full chapter of less tense, not critical stuff from the perspective of some other character, before I can get to the resolution of the conflict I was reading in the first place.

This completely breaks the pacing and pulls me out of a novel. In Wayfarers 1, at least, the focus of the plot was still preserved even when the perspective changed - here, the focus of the plot changes between two major characters, which is endlessly frustrating whenever cliffhangers are the common way of ending a scene, only for them to be swiftly resolved thirty pages later at the start of the next chapter told from the same perspective. This device cheap and sours an experience that would otherwise have been very enjoyable.

I still definitely recommend this book, but because of the above can not in good conscience give it a perfect score. If you have more of a tolerance than me for that sort of thing, though, you’ll find all of the great aspects of Becky Chambers’s writing are still present here.

Bird Milk and Mosquito Bones, by Priyanka Mattoo

This year, I tried to continue my tradition of reading wide, and looked to find a section of books that was different from what I’d previously read. I also had not read a lot of non-fiction yet, so when I found Bird Milk and Mosquito Bones, I thought I would fulfill two needs in one go, with a memoir from an author who was born in Kashmir, a region of India. I know very little about Indian culture and customs, so I figured this would be a good opportunity to learn.

As often happens when reading about something so distant from my own experiences, the book did not click with me at first. It wasn’t just the Indian way of thinking about the world that was alien and novel to me, although I am sure that played a part - it was also that Priyanka Mattoo often moved too far into the realm of the purely informational for it to stop being relevant context, and start being too much for me to take an interest in. An example: the author’s family tree was often expanded upon in a lot of detail, and I frankly could not keep track of who was someone’s brother, uncle or great aunt, nor did I particularly care.

Fortunately there was still enough, even in the first part of the book, to keep me interested. I found it particularly interesting to see the parallels between Indian culture, their wedding customs, and the way they view interpersonal relationships, and Portugal’s own matriarchal culture. Of course, as any reader, I reach to create parallels with my own world to make sense of the new, and I found some here that I was not necessarily expecting.

All that said, up until about the halfway point of this book, that was all I’d gotten from it - some interesting nuggets of information about Indian culture, interesting in their own right, but nothing beyond that. The latter half of the book changed that. The subject became more universal in my eyes, as Priyanka Mattoo went about describing her struggles to balance the love of art and creativity with the needs of a capitalistic world. In a related line of thinking, Priyanka Mattoo also went into great detail about the multiple times she realized she hated her job and the depression it gave her. The author is clearly much farther ahead in life than I am at the moment of writing this, and the fact that I related so much to her young experience of taking refuge in books made me more keen to take note of the ways she found her path and ways to deal with problems that I, too, am facing. Perhaps one day I can also find the strength to chase what gives me joy more fully - I write as I labor away in tech, which I do not fundamentally hate, while still my passion rests elsewhere. The prose is beautiful, written with a conversational, magazine-style intimacy, and metaphors often struck a chord with me: for instance, the idea that resilience, when it becomes permanent, becomes endurance, a rubber band permanently stretched.

At the end of the day, this book made me, a 29 year old cis white man, feel a deep sense of kinship with a 50+ year old Asian woman. That is the best possible outcome to get out of the attempt to widen my reading horizons, and is ultimately all anyone can ask out of a book, doubly so a memoir.

Cue the Sun, by Emily Nussbaum

Cue the Sun is a Pulitzer-prize winning book exploring the invention and history of reality TV, and it definitely lands itself in the group of “books that taught me something”. Reality TV has a perverse fascination for me - it’s hellishly appealing (I write as me and my wife watch the occasional run of Below Deck or Naked Attraction), but it does come with a feeling of being sleazy in some hard to pinpoint way. Exploring whether that comes from cultural indoctrination or from legitimate grievances is part of what this book helped me think about.

Cue the Sun starts by putting into words the alleged reason for the appeal of reality TV - the fact that real people get put into high pressure situations, creating nuggets of authenticity that are usually not available to a viewer of non-reality, scripted television. Even the best scripted television, it is argued, can achieve that rawness only in a more literary, affected way and not in the pure form that reality TV achieves.

Of course, this is a thesis that the people involved in writing, producing, editing and contributing to reality TV reinforce throughout the book (even through multiple ethics violations and questionable decision making processes), half as a justification for the things they’ve done and half as the rationalization of the genre’s artistic value, a permanent response to the chip on their shoulder. However, it is a flimsy excuse indeed, and one that perhaps finds better expression in purely voluntary shows of similar rawness nowadays - livestreaming, for example, allows for similarly raw forms of content to exist without the influence of network executives and drama-hungry producers.

And really, even if one thinks of it as true, it is surely not the whole story. As I read through the book, I couldn’t help but feel like the rawness was part of the appeal, yes, but that leaves out a lot - the other part of the appeal is the transgression itself, the fact that these are mediums where many things that were not usually included in scripted television made their way into people’s households. In this way, the public perception of the medium as sleazy is self-serving, and allows them to get away with more. Perhaps, in a way, the rejection of mainstream criticism and the accusations of snobbery are also something the genre indexes into itself, as a way to distance itself from the shackles of normalcy that would have killed the more sordid side of its appeal.

In any case, what I kept asking myself as I read this was if the bad (the manipulation of contestants, the “pebbles in the pond”, and the ruthlessly capitalistic destruction of the integrity of the medium with stuff like “Frankenbites”, an audio clip that presents itself as a single, contiguous line, but is in fact built from several disparate recorded audio clips edited together) was a necessary feature for that rawness, and when exactly it stops being an excuse for all of the nasty subterfuge the medium was up to. Understanding is fine, but these are no saints or inconsequential cultural phenomenons, and I can’t help but walk away with the sensation that at the end, many of the people involved in reality TV’s creation and evolution rationalize their own participation under the guise of artistic merit. They paint the medium as being some revolutionary vehicle for the capture of authenticity, when the history of its evolution seems to be a move away from that authenticity, and a failure by everyone involved to protect it from the capitalistic impulses that make for nasty, sordid drama. This was most evident at the end, when the author compared the generation that grew up on “An American Family” to the generation that grew up on “Keeping Up With the Kardashians” - the phoniness is built into the latter far beyond how it was built into thee former, and so the argument for authenticity and rawness to legitimize the medium starts holding less water. And if the argument for authenticity starts holding less water, then the moral standing of people involved in the medium starts being less grey and more properly blackened, pardon the pearl clutching. Especially once we reach the harrowing last chapter about Donald Trump’s The Apprentice, and realize just the breadth of impact the genre can have with its irresponsibility. At some point, it becomes inexcusable (and I lean towards thinking it happened far before The Apprentice). The author feels sympathetic to the medium and to the people working in it, but in the end fails to make a good case for them - the objective facts of her account overshadow the sentiment of value, and make a pretty good case for the opposite: that this is a rotten, irredeemable group of people, fueled by base instincts and ambition at worst, and by recklessness, absconded responsibility, and naivety at best. If such was not true at first, then certainly shortly after the genre grew its claws.

It made me think of parallels to software engineering, and how fields can be co-opted by business impulses to the detriment of people in the industry, eventually alienating the people actually doing the work, and forcing them to come to terms with a decision: continue to be complicit, or swear off the thing? I am not a moral judge, so I would understand the former, especially if they were getting piles of cash (which most people here, bafflingly, weren’t; instead it’s more as if they actually drank the Kool-Aid), but at least have the intellectual honesty to admit you sold yourself out. That honesty is almost entirely absent from everyone working in reality TV in this book, instead replaced by an effort to take hold of the narrative and conjure up some moral redemption.

An hilarious bit of unnoticed (by the author) irony happened when the book described the feelings of betrayal by the part of groups of reality TV laborers when they were thrown under the bus in negotiations by the Writer’s Guild of America. You know, the same writers whose picket struggles they’d been undermining, by allowing the networks to use their content (which, by and large, does not need a script to be written in advance to the same extent) to bypass writer’s strikes. Class solidarity for thee, and all that. Stings when it hurts you, I suppose; but to use this as a way to paint the reality TV workers as sympathetic victims of a backstabbing showcases the same lack of self awareness that permeates much of the industry.

All in all, this is a well written, thought provoking book, even though it falters a bit in the middle, threatening to turn into a collection of anecdotes about the genre and sort of losing track of its own guiding plot and connections for a good while. It finds its stride again by the end, when it abandons anecdote for the sake of anecdote and again focuses on the implications of the genre, ethical considerations, and gathering the perspectives of those involved (this was most notably absent, for example, in the chapter dedicated to Survivor, which read more like an historical account).

If I can fault it for something, it is that the author is a bit too saccharine in her depiction of reality TV participants, all the way to the epilogue - ultimately, while her depiction gives them more human depth, and deeply contextualizes them, it also paints them as the exact type of sleazeball you would expect from the genre, and fails to ever properly come to terms with their nature as poignantly as it did, for example, for Mark Burnett and Donald Trump, during the book’s final chapter.

How to Blow Up a Pipeline, by Andreas Malm

This is a tricky book for me to talk about, because it is one where my position is different from the mainstream, and one that is hard to transmit to the general population that grew up, mostly, in times of peace. However, it is a deeply necessary book. If you’ve read my review of If Nietzsche were a Narwhal, that I wrote about last year, I faulted it mostly for having a doomer kind of attitude towards climate change and problems to come from it, and excusing itself from proposing a path forward.

Well, this is a proposal for a path forward. But it is not pretty.

Andreas Malm’s central thesis is, put simply, that meaningful change cannot happen without violence. That much should already have the alarms ringing for a lot of people, so let me clarify immediately that he means simply violence against property, not violence against people. Violence against people is inexcusable.

As I say that this is a hard book to write about, I find myself having surprisingly little to say about it. That’s it, that’s the book, that’s the thesis: if we are to really fight the climate crisis, violence needs to escalate; pipelines need to be blown up, and airplanes grounded forcefully, and bottom lines meaningfully impacted. Most of the rest of the book is an exploration of how this was true for other meaningful societal change: for the sufragettes movement, for example, or for the Civil Rights movement (how can one forget that there would be no Luther King Jr. without Malcolm X paving the way). Then, a portion of the book is dedicated to exploring why this has not happened more for the climate crisis, when we are so deep down that road already, and the strategies for suppression of outrage that have been employed to make this sort of violence unpalatable in the eyes of the public.

As I write this, this year, a group called Climáximo (kind of like a local Extinction Rebellion) has started taking this sort of action in Portugal. They slash the tires of SUVs and ground commercial passenger planes. They break the windowpanes of stores and are a nuisance to ordinary people. I have seen the general populace around me complain about them, say things like “this is how you get people to stop supporting your cause”, and I have struggled with it; because in my mind, Malm is absolutely right, and that level of action is necessary to open the door to more peaceful dialogue causing meaningful change. Meaningful societal change does not ever happen peacefully, and so I am grateful these people exist, insofar as they keep acting on property, not people. But seeing the reaction of people around me to them shows me just how far along the class struggles we are; as the people who will be most affected by climate change complain about the people actually trying to fight it with the proportional level of action, dismissing them as privileged far-left extremists who have nothing better to do with their time. This is no more than class struggle, of course; it serves the privileged elites very well to have people think so, and it is no wonder that fossil fuel tycoons have been pouring billions into spreading those narratives for decades now.

I have said enough here, but I will end with this - if you are one of the people who thinks some vein of “we must fight climate change, but not like this”, I urge you to read this book, and try to reconcile that perspective with the sense of helplessness, of “we aren’t doing enough”, that me and many others feel. For my part, I am glad these people exist, and I am glad Malm wrote this book - and I see in it a possible way forward that I had not seen before. For that, I am thankful I read this.

Klara and the Sun, by Kazuo Ishiguro

Continuing the effort to read wider, this was my first Ishiguro novel, and I had read no other japanese writers besides Haruki Murakami.

The prose of this Nobel laureate is surprisingly accessible for how dense and packed with meaning with is, and for how alien many of the things being described are. I wonder how much of it is lost in translation, or added in translation, because it carries a lot of the same mystical feeling I’ve gotten when reading Murakami - is that a trend across Japanese writing or something that results of the mechanics of language transposition? In a way, this felt like reading a Murakami that is far more competent at taking themes and allegories to good port.

It is a delicate novel, never really jolting forward as much as it moves tenderly from theme to theme, with Klara at the center. Klara, an android companion made to serve as human children’s friend, was a very interesting character, as we follow along her attempts to learn what it is to be human; not because she necessarily wants to be one, but so that she can understand the child she is supposed to befriend.

Ishiguro exhibits the restraint that Murakami lacks, and only shows me exactly what is important for the points he’s trying to make; this gives the sense that the world beyond Klara is much deeper and more intricately developed than we ever actually get to see. It’s a delicate construction where the interesting things are left aside for the important ones, and the end product hits you less in the face, is less like a great orchestral rise and more like the calm end of a long walk; but it lingers just the same, not needing that sense of the grandiose to have the humane latch onto your brain. I did think it did not wow me or give me any great insights on human life, though - in many ways it seemed almost common sense, if very beautifully written common sense. The Mother was the most interesting character, but she was addressed with a sort of romantic handling that perhaps left a little bit of her interesting inner life to be explored. There is a reluctance to truly go into the deep end, to break the calmness and tackle the real demons, that works as an aesthetic construction but left me a little disappointed. For this reason, I started by giving this book 3 stars - but there is something about its aesthetic that grabs hold of you, and I found myself still thinking about it months later. Because of that staying power, I bumped it up to the four star group. I do not quite grasp yet why it lingers so; I think it is the presentation that does it, but it comes unannounced, with no great metaphysical questions, just a thought of it like one thinks of a lazy Sunday afternoon long ago.

Klara is a touching, and pretty book. It is not a deeply clever one, nor one that tackles any great human angst with the depth that it may deserve in other writing. But it is a book that tackles it gently, and with a sense for the beautiful. Sometimes, that is enough.

The Haunting of Hill House, by Shirley Jackson

A surprisingly contemporary book, with dialogue that’s much more relevant and recent than I expected. The main characters are genuinely funny and have remained relevant to today - I don’t know why I expected this to be more anachronistic. Perhaps in my mind it was more closely tied to horror books of the 17th century, and I expected it to feel as anachronistic as Poe and Lovecraft, but it feels far more modern than that; definitely an easier read.

I can definitely see the markings of Stephen King getting his inspiration here to go on and write The Shining here, but I ultimately feel like that’s the better book. Nevertheless I recommend this for a masterful atmosphere, funnily set up characters, some moments of excellent prose, and a very interesting character study in Eleanor’s progression inside Hill House, that preys on her insecurities in the most competent way possible.

The characterization of Eleanor is great and the slow corruption of her thought patterns by the house, especially evident in her interactions with Theodora, cannot be faulted in any way. There is a strong sense of foreboding permeating the book, which is beautifully written and serves that sense of foreboding throughout; for instance, with perhaps the best opening to a horror novel I’ve read so far.

It is effectively not very scary, though - the horror comes from the foreboding and the situation the characters find themselves in, but compared to more recent horror books, there is nothing here as horrifying as Pennywise or as the moral conundrum of Pet Sematary. It is effectively just tense.

The Long Walk, by Stephen King

What, you thought you were getting through the 4 stars without a King book making it in? Silly you. I continue on my quest to read all of King’s bibliography, a few books a year. It would be very helpful to that endeavor if he could stop publishing books nearly as fast as I read them. But I digress.

The Long Walk is deeply interesting, like early Stephen King has gotten me used to. If you would have told me that you could have a whole book around the simple concept of a walk, where the last one to keep walking gets anything they want, but everyone else gets shot, I would have thought that it was quite hard to do. In fact, my first instinct would be to pepper it full of other references to things happening outside the walk - the inner lives of parents, flashbacks, etc. Instead, King makes it entirely about the Walk - it starts with the Walk in Chapter 1 and never relents or looks away until the end. The inner lives of the characters are rich, and they all represent different fuels, different ways you would approach it, different inner dialogues that would push you to keep going even when there is nothing else pushing you to keep going. And the horror comes, of course, in realizing the extents of rationalization that you would go to - maybe it’s not so bad to sit down and let yourself go. Maybe it’s preferable to whatever it is that’s happening. After five miles, surely not. After fifty? Maybe. Five hundred? Surely. How far would you go?

From the randomness of some of the deaths - a cramp, the runs, a pneumonia - to the deeply engaging inner lives of most of the characters, all of them reflecting some of our own thinking back to us, to the perverse fact that the Walk makes friends out of all of them, and that makes it far harder that one of them alone can win… and to the fact that they all have different reasons (believable ones) to have gone on the Walk in the first place, the book has a solid grip on you and you can never really look away. It is not as grand in scope as It, and the design of it means you are limited in what you can see of the characters (you can never see what happens to them before or after thee Walk), but it is a laser focused, terrifying book. If you are a fan of the kind of horror that comes from self insertion, from thinking of how you’d react in those situations, this one is for you.

Caledonian Road, by Andrew O’Hagan

Caledonian Road is a book that seems like it was written by your 70 year old English Literature professor, trying really hard to come to terms with, and include, recent themes - like TikTok, meditation apps, and cryptocurrency. That comparison holds on so many levels, too. It’s not like the book is bad; it’s well written, and shows a deep mastery of prose and style, but it is dripping with how do you do, fellow kids kind of energy; it shows that the author does not come from this world, and his words come across as well researched, well sourced, and always technically correct, but affected and artificial.

The main character of this book is Campbell Flynn, a celebrity writer and academic who owns a house in Islington’s Thornhill Square, is completely obsessed with money, and writes a self-help book called Why Men Weep in Their Cars that ends up getting too much negative press because they are Flynn being honest for the first time in his life.

If the above doesn’t hint it for you, there is one serious gripe that I have with this book, which is the same gripe I will have with Yellowface, the worst book I read this year. The gripe is this: even if it is intended, and it definitely is here, everyone in Caledonian Road is a hecking dreadful person, and I don’t want to read about them for 400 pages - even if the book ends up being a tragedy and they all get their comeuppance for how insufferable, vapid and misguided they are, in their high society bubble, it is simply too dreary to withstand those pages until we get there. Schadenfreude can only get you so far, and making one dislike all of your characters to set up that schadenfreude also risks, you know, making one dislike your book, since one hates everyone that is a part of it.

I do think this is better than other instances of that, and I am being quite harsh to a book that is genuinely well written throughout. There are some very nice moments in it, and I found the depiction of the Eastern European human trafficking operation into London particularly interesting and touching. But at the end of the day, as much as I can recognize a lot of its merits, it’s not a book I enjoyed, and so it is hard for me to fervently recommend it.

Dracula, by Bram Stoker

Note: Dracula needs no introduction, and it also needs no reservations. The below review contains heavy spoilers. I consider that long enough has passed for me to talk freely about the plot points.

The book is well written enough, although relatively anachronistic in the expressions that it uses at times, and occasionally slipping into stylistic types of prose that are hard to follow (especially the ones from the Irish shore, or the peasant dialect of people who speak very differently from the named, main characters). It is told in a sequence of journal entries from several different characters, as well as newspaper clippings and other writings - never with a narrator. This allows the perspective to shift between the different people involved in the story, although act 1 is mostly told from the perspective of Jonathan Harker. Later Jonathan takes the backseat, and it is mostly the doctor Seward, Mina Harker and Van Helsing that take the reigns of the narrative (although Jonathan does have some appearances still).

Act 1 functions as a pretty interesting horror tale, where the solicitor Harker gets roped into visiting Castle Dracula, where the Count is attempting to plan his move to London. After seeing a little bit too much for a mortal, he is in dire straits, and the Count is planning to end him. Through a bunch of cunning and daredevil behavior, Jonathan manages to escape. We then move on to Lucy’s perspective for act 2; she just so happens to be Mina Harker’s friend, and ends up becoming one of Dracula’s first victims after he arrives by boat. Eventually she turns, and an end must come to her, to save her soul from being Undead.

The book has strong religious overtones, and the Count is often described as being of the Devil, as the people fighting him are describing of being Godly, and drawing on the will of God to fight the Count’s nefarious influence. Lucy’s act 2 evidences one of the first nitpicks I have about this book - there are a little bit too many hard to justify coincidences. Lucy just happens to be Mina’s friend; and Dracula just so happens to attack her first of all. It is definitely excusable, but noticeable.

The characters all rely deeply on Van Helsing, to the point of it being silly at times how careless they behave. At one point, even after being explicitly told to stay with her all night, doctor Seward decides not to and to instead leave someone else tending to her; this, of course, ends up with Dracula feeding on her. This sort of thing happens multiple times, where something is clearly a bad idea or a needless risk, but it is taken anyway, ultimately leading to Lucy’s death.

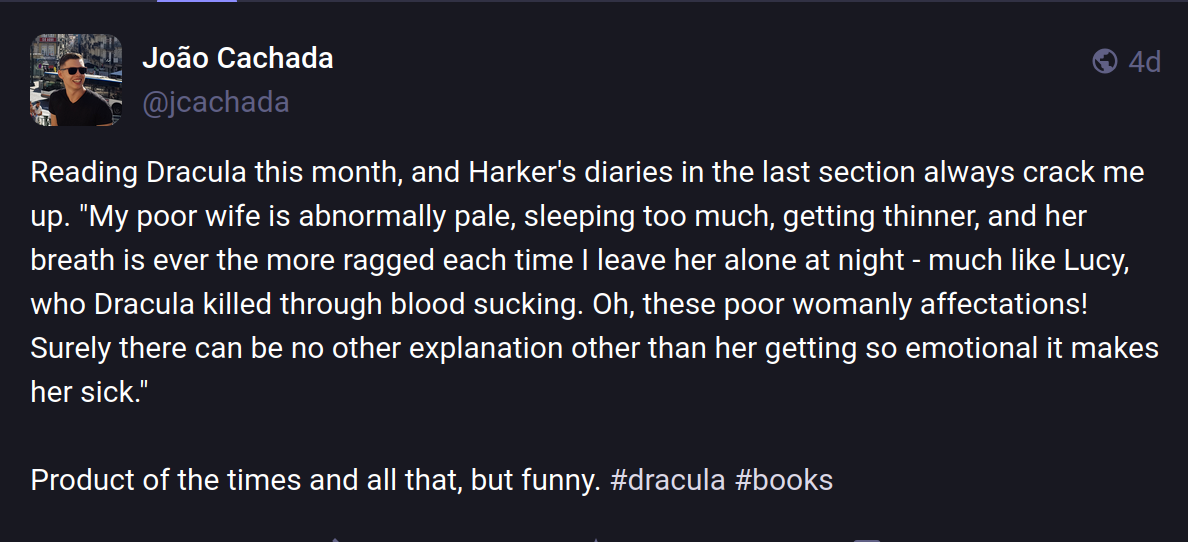

Later in the book the same sort of thing is present, in fact having led me to post the following:

The book is, of course, deeply sexist, a product of the time; but in a way strangely progressive too. Mina Harker is reduced simply to the role of the wife, even though she is the most capable among the men; but there is something to be said for the fact that she is, in fact, the most capable in the first place, the cleverest, and the one who bails them out multiple times by deducing, for example, where the Count is.

The book is, of course, deeply sexist, a product of the time; but in a way strangely progressive too. Mina Harker is reduced simply to the role of the wife, even though she is the most capable among the men; but there is something to be said for the fact that she is, in fact, the most capable in the first place, the cleverest, and the one who bails them out multiple times by deducing, for example, where the Count is.

The novel is coated in a vaguely homoerotic tone; there is rather a very strong conception of male friendship, which according to my edition’s contextual snippets at the end of the book, is something Bram Stoker was a big proponent of (buying into Walt Whitman’s ideas of society flourishing through the strength of platonic male bonds). In fact, all of the men in the book share a deep sense of camaraderie and a bond of friendship that is not particularly common nowadays, and that makes everyone be willing to die to help Jonathan and his wife escape the talons of Dracula.

The novel is, however, deeply sensual, and the terror of the Count and his host of vampiresses is tied very closely to lust, with the vampire’s kiss bringing people to the brink of orgasm, and the vampiresses causing such a reaction that they almost stop Van Helsing from killing them, simply by looking at him. Much has been written about vampires as symbols of lust, but for the time, and at the same time as Bram Stoker was writing essays against pornography in fiction, this is a yearning way of writing them; and perhaps hints at Stoker’s own repressed sexuality.

All in all, the book is not touching and I was never particularly moved. I also thought it dragged a bit, especially by the final act, when building up to the confrontation with the Count. It is, however, memorable as a foundational tale of horror, setting the scene for one of literature’s most famous monsters, and so worth a read as a time capsule, if nothing else, and enjoyable enough as one, too.

Fever House, by Keith Rosson

This is a novel that a lot of people will really enjoy, even though it’s not necessarily for me. It was brought to my attention because Stephen King apparently recommends it often, and so my friend Borna sent me a TikTok of that.

It is fundamentally a thriller that becomes, after a while, a horror book. It reminded me in a lot of ways of Guillermo del Toro’s The Strain, with the caveat that this is a little bit more guarded with the “devolves into horror” bit.

The writing is good and tense, although it took some getting used to to come to terms with the fact that the book is written in the present tense. It is written very cinematic, with very short sentences and a distinctive style. The writer writes like a noir author. He picks up the pen. Thinks about what to write. Jots down something. Kind of like that.

There is a lot of things to like in the plot and a couple of the characters are genuinely well developed, even though a couple really aren’t. Katherine Moriarty and the hulking side-kick of peach (the brute whose name I don’t remember anymore) are particularly good characterizations, and her son, as well as the detective whose name I also don’t remember anymore, are particularly grating ones. It’s not particularly a good sign that I remember the archetypes, but cannot remember the people; that rarely happens to me.

I suppose the main problem that I have with the book personally is that it goes a fair bit past the body horror and gore aspects, and straight into misery porn. There is no particular theme to it besides “bad things happen, and when you think they’re not that bad, they get worse”. It’s an unrelentingly cynical escalation of things going wrong, and for me I could not find a particular point to it - the characters are well written, but they don’t go anywhere or grow in any meaningful way, their arcs aren’t of growth, and the most you get out of them is some catharsis in the form of vengeance. There isn’t any of the heart that guides an It, or a The Long Walk, or a The Haunting of Hill House. It achieves horror, but in the way that a (admittedly well written) LiveLeak video achieves horror - it’s horrifying, but I don’t really want to look at it in the first place.

That being said, it is engaging and it will hold your attention, even if there is no particular payoff or anything beyond the twists. Horror fast food.

Firestarter, by Stephen King

An interesting book, mostly suffering from a weaker first third. We follow the story of a father running cross country with his daughter, being chased by a shadow government agency that experiments on the supernaturally activated; we learn, through a series of flashbacks, that this supernatural activation has come from a government experiment ran on college students (one of them was our protagonist), and that by stroke of bad luck, when two people who took part in the experiment have a child together, there is a chance they are particularly supernaturally capable, as is the case for our titular firestarter.

The story starting in media res is a good decision for the pacing, getting us right into the action from the start. But the flashbacks that slowly build up the history of everything that happened break the flow of the chase, and often feel like a chore you have to get through to get back to the tension of will they be caught or not. Much like in A Close and Common Orbit, the main problem here is not necessarily that the flashbacks are not interesting, because they are fine; it’s that they inevitably come at a moment where the action is somewhere else, and I want to know what happens next in the plot thread I’m following, not take a detour down memory lane and pause to look at the protagonist’s college days.

Once we’re “all caught up” and the focus is on character interactions, the book is quite enjoyable, and if it were not for the first third being such a drag, it would probably rank higher and among one of King’s best. For the entire second half of the book, we see a ruthless villain try to break the mind of the Firestarter through sheer manipulation, and it is masterfully written and interesting throughout. The book also contains what is probably one of King’s most harrowing scenes - and it effectively marks the moment the book ramps up into the most interesting bits. And what’s more, it’s this burned into my memory even though I knew it was coming about 200 pages in advance. Great stuff.

In any case, this is a good book, defrauded by one of King’s weakest starts to date; so stick with it, and better it shall get.

Holly, by Stephen King

Look, I’m not going to lie - Holly is starting to get pretty old as a character. I understand King loves her, but the feeling is not mutual; in fact, it feels like King might love her in part for the novelty of writing such a “young” (chronologically speaking, meaning modern) character, when much of his work is often more anachronistic. But I know people like Holly. I went to university with them. They’re part of my friends group. And because they’re such familiar ground for me, they also become far less interesting to read about when written by an author whose major strength is character development, and exploration of spaces in the minds of characters that other authors either don’t dare go near, or cannot do justice to as elegantly.

Beyond Holly as a character, this is a pretty run of the mill detective book, about in line with The Outsider. The mystery itself is engaging enough - the old academic cannibals a bit tripe and never particularly scary, with one of them being comically racist (as if being a cannibal wasn’t good enough of a reason to dislike her), to the point where she becomes so out there that she can’t even be scary - not in the same way a Hannibal Lecter can, for instance. The story beats are strong and this is a competent thriller, but not really much beyond that.

Piranesi, by Susannah Clarke

I was quite bored at the start of the book, and I feel like the first act, of establishing the way that Piranesi interacts with the House he inhabits, drags enough to become masturbatory in the descriptions of halls and statues that surround him. Introducing us to his habits is laborious, slow and contemplative in a way that is definitely intentional. Perhaps I wasn’t in the right state of mind for it, but for me it made its way too far into that territory, and well into losing my interest - I found myself hoping something would happen to shake up his routine.

The book picked up considerably when 16 got involved, and pretty much everything from there was good and engaging. The build-up was satisfying enough, with plenty of hints and a slow, easy build up with the Other as villain being quite an obvious thing from the start of the novel, but still one you feel yourself inexorably drawn to, like waiting to see a horror movie play out.

At the end, though, it is Piranesi’s gentleness that I remember from the book, and his interaction with Raphael, the police officer. Piranesi is lovingly portrayed, and I cared for him when he realized that his longing for more people was also the inevitability of hurt to enter his life. He was deeply emotionally mature even if he was deeply naive about the world, and that juxtaposition gives the novel heart. It’s just not quite enough to fully make up for the initial slog.

Snow Crash, by Neil Stephenson

Snow Crash is an interesting book. I very much did not like it at start, especially when just establishing Hiro Protagonist and YT as characters. The writing is so heavily stylized in cyberpunk that I couldn’t quite be sure what was satire (really, everything is dripped in satire) and what I should be taking seriously. The book toes the line very effectively between being a parody of a hyper capital future and a scathing science fiction critique, but it is a strong culture shock to start reading, and takes a while to get accustomed to.

On top of that, the start of the book drags. Nothing particularly happens. The book revels in its Cyberpunk setting a bit too much for my taste, self-indulging in the descriptions of the mega franchises (franchulates, as they are called in the book), in the drawn out descriptions of people’s avatars and their Metaverse houses. For the whole of the first third, you’re getting style over substance, and I was starting to lose interest.

It does, however, pick up - particularly when it starts approaching the concept of the Tower of Babel, and exploring the idea of the neurolinguistic virus. I will say, even after it picked up,I was constantly annoyed by the insistence on describing yet another make up of a franchulate or just how futuristic Hiro’s new bike is supposed to look, when really I wanted to get on with the story. I imagine this was all quite moody and trendsetting back when this book came out, but it reads as a hindrance to the point nowadays. But ignoring that aside, the book does find its groove and I ended up enjoying it once it got going. Whenever it focused on the actual neurolinguistic virus plot more than on the vibes of the franchulate-ridden cyberpunk dystopia, anyway.

Another redeeming factor is the fact that Stephenson can be genuinely funny at times, both in one liners and in the construction of the story itself (the build up to YT’s Dentata and Raven’s reaction to it being particularly amusing to me).

I did feel like the ending did a relatively poor job at providing me closure for any of the characters, but then again, I guess closure would go against the vibes of the Cyberpunk, man.

Maybe I’m just not a big fun of cyberpunk as a genre - I’m starting to suspect that at this point, anyway, as the things I tend to take issue with (the cynicism as a point in itself, the over-indexing on style, etc.) are things that tend to be transversal to other classics in its history.

The Adventures of Amina Al-Sirafi, by Shannon Chakraborty

This is an interesting book that I chose specifically because it ticked some boxes I don’t usually tick with my books - it is a pirate story, which I don’t read many of; it’s a fable or great adventure-style myth, which I have enjoyed a lot in the past but have not read much of recently; and it is also a Muslim book, which is something I don’t usually read. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not like I have never read books with Muslim representation, but this is a book where all the main characters except one are Muslim, the villain is Christian, and the culture is steeped in Islam and Indian sea culture, which is far from the more anglicized literature I usually read.

It is a well written book that makes use of a structure similar to The Name of the Wind, being told from the perspective of a scribe that is putting down the story of Amina Al-Sirafi while directly talking to her, so there is an element of mythologizing itself and of the ego that comes with legend. This carries over to the actual story, with Raksh, the protagonist’s ex-husband, being a demon that preys on her lust for a legacy, glory and riches.

The book’s prose is good, although I felt like the editing went down in quality as the book arrived at its last third - at that point there were a couple of typos, sentences that became too long, and weird grammatical constructions.

Now while the book is competently written, and for the most part I enjoyed the flow of the action and was never particularly bored, a few things stop it from placing higher:

- there are a couple of Deus Ex Machina in the last third of the book that I was not happy about, and which I will refrain from commenting on specifically to keep things spoiler free. There were hints that these might be addressed in further books, but in this one they just came across as gifts from God that solved the main problems for the main characters without them earning it.

- the central conflict of the main character Amina is in how she struggles to balance her lust for the open sea with her desire to be a mother for her child. This tension never gets properly resolved - Amina simply leaves and agrees to being moved away from her child, and all we get is a comment from Majed, her navigator, saying “there must be a way to make this work”. No resolution, no real grappling with in any way besides feeling the emotional strife, and very little character development, besides Amina admitting to herself that she does crave adventure, something she did already in the first few chapters of the book.

- Raksh is a puzzling character - he is described in the first half of the book as a deeply scary and dangerous demon, and then after he shows up is largely incompetent and useless. I suppose he gives Amina luck - but I never saw much of said luck after he showed up, perhaps because it needs to be forgotten for the Frank to actually be a serious threat. He is useless in combat to an hilarious level, which makes me wonder how any of the pirates were ever scared of him in the first place, and how Amina’s inner dialogue makes him so much of a beast in the start of the book. It made me feel like that was only done for dramatic effect.

Besides those main gripes, the book was generally interesting, well researched, and well written, and I do not regret reading it, as it enriched my understanding of the Indian sea, the mythology surrounding it, and the folklore of Islam with a strong emphasis on conceptions of God, a literature I’m not usually exposed to.

The Stinkers

I don’t usually comment much on the books I didn’t find very good on a given year, but I feel like this year I want to. I want to because the two books I’m placing at one and two stars are broadly beloved books with wide audiences and many merits, and so I want to expand on why I don’t exactly think, at least at this time of reading, they work for me. There are heavy spoilers for both books below, so read at your own peril.

Project Hail Mary, by Andy Weir, was recommended to me by my partner, who really enjoyed it. I feel less fond of it. Weir has been described as the Dan Brown of nerdy reddit users, and I think that kind of fits - though it’s somewhat unkind of a description. His writing and prose are definitely better than Brown’s, and I’ve been told the science is quite accurate (at least the microbiology part, as my partner is a microbiologist - I wouldn’t know myself, and especially can’t tell about the physics).

First, the positives: the character of Rocky is great, the prose is easily readable in an “airport novel” kind of way without ever getting in the way, and there are some genuine moments in the book where the tension ramps up enough that I was engaged and hooked on figuring out what was going to happen next (like when the Taumoeba gets into the fuel). Finding out about the particulars of Eridians, their anatomy, culture, and ways of seeing the work was definitely interesting.

The neutral: the humor. Andy Weir writes most books as if his protagonist is Tony Stark. He is the writer equivalent of Joss Whedon’s. I find it tolerable, but sometimes grating. Some people love it, some can’t stand it.

The negative: Ryland Grace is one of the most frustrating main characters I’ve read in a long time. He is meant to be flawed and human and relatable, but he is really just insufferably incompetent to the point where I was almost rooting for the Astrophage. If not for Rocky, I would have really struggled to complete the book. Example: at one point in the book, he decides to undertake an extremely risky maneuver to turn on a centrifuge manually and create artificial gravity, using only the thrust of make-shift engines duct taped to the outside of his ship, against the advice of Rocky, because… he’s impatient. He doesn’t want to wait for 11 days of space travel at a normal speed. That’s it. That’s the reason. Jeopardize the entire mission to save two planets and billions of lives because… you’re antsy. Just… what?

Throughout the book he is consistently incompetent, inconsiderate, obnoxious, and mostly exists as a way for the author to proxy the vomit of factoids that need to be shared with the reader.

That’s another thing - I will consider this a neutral since clearly some people love it, but the way the science was exposed was clearly not for me. Often it felt like there was no narrative significance to the particulars of the science that I was being given, and the author was just looking for excuses to share cool things with me. Fine if that’s your thing, but it does nothing for me. It often felt like I was reading a Wikipedia entry in the middle of a story.

Stratt is laughable. She is an American fantasy of how bureaucracy is the ultimate evil and if only someone could get given ultimate power and immunity from consequences, surely shit would get done once and for all. She is a childish, ridiculous, strongman representation of how adults would deal with a crisis scenario.

Last but not least, my final (big) gripe with the book was the ending. The only possible character growth for Ryland had to do with his cowardice. After the reveal that he was not at the Hail Mary voluntarily, I thought that it actually explained his woeful incompetence throughout the novel. His one redemption was that he went back for Rocky, sacrificing (to the best of his knowledge) his own life to save his friend - transcending his cowardice and showcasing some character growth in the form of bravery. Yet that character growth is thrown away when he then decides to stay at Erid because he is afraid of the journey back to Earth, and afraid that he will go back to find a planet that has not survived long enough to be saved. He is, ultimately, still a coward, and I find it deeply unbelievable that he stayed for decades in his dome, without light or the ability to get out and have meaningful social interaction that is not mediated by a xenonite wall, without going insane. This is the man who got too antsy to wait 11 days. Now he’s greatly self entertaining for decades?

The ending was neither satisfying nor believable, and that frustrates me in proportion to how many things I found to like in it. It is a book full of potential, but ultimately does not live up to it.

Yellowface, by R.F. Kuang, is not a badly written book, especially if taken as fundamentally a horror story. However, even if it is not badly written, it is not well written. The prose is not particularly lyrical and the metaphor is mostly zoomer colloquial speech with not much artistry to it. I don’t remember a single memorable line from it, even though it’s not aggressively bad. Several moments lend themselves to having better lines too, like the confrontation at exorcist’s steps, or the visions of the ghost of Athena by the main character, Junie. I can’t help but feel like if someone like Stephen King was writing this, those would be harrowing, beautiful, scary. Instead this feels like the Gossip Girl version of writing those scenes, always moving on just a bit too fast, always glancing away from the interesting things to zoom in on the trite. One could say that is in line with Junie’s character, and props to the author if they are actually an excellent writer and are just being faithful to the character’s voice (the protagonist is, indeed, the Gossip Girl version of a writer), but it doesn’t make it any less insufferable.

Which brings me to the main point of contention with the book as a whole - everyone in it is fucking dreadful. Junie is an awful person throughout, not just from the central crime of the book in which she steals a best seller, but through and through. She’s unkind, selfish, a champion at rationalizing her own shitty behavior, and someone so extremely tiring in how terminally online and deep into identity politics she is that I am just exhausted of her. I would not ever be friends with her. I would not even want to interact with her for longer than five minutes. And perhaps because we see everything from Junie’s perspective, or perhaps not - everyone else in the book is fucking dreadful too. Everyone is either supremely self serving, like Daniella and everyone else in the publishing industry, criminally dumb like Brett and Junie herself, terminally mean like Junie’s mom, or painted as criminally uninteresting for being vaguely normal, like Rory and her husband. The only glimmer of kindness that the whole book had was when Geoff, the disgraced ex-boyfriend of Athena, reveals how much he suffered from dating her. And that was not a lot of it. I was just so starved of any humanity by that point that any nugget felt like a lot.

And yeah, maybe that’s part of the whole ethos of the thing, but I’ve always found it pretty close to cowardice when authors can find no redeeming qualities anywhere in their books - it cheapens the horror for me. There isn’t a lot of it to begin with - the main conflicts Junie goes through are mostly self-inflicted and in her own head, which wouldn’t be enough to dismiss them, except that she’s so fucking insufferable that what do I care what she inflicts upon herself?

This is not to say the book is unbelievable. People like these exist, I am aware. And they probably go through the plights that Junie goes through in this book.

I just don’t want to interact with them, and I’m not particularly fond of reading about it either. This feels like a book that gave me a window into the life of someone so addicted to Twitter that I want to keep a reasonable distance from them at all times.

The climax of the novel was laughably bad - you can see it coming from a mile away that someone is using Athena’s voice recordings to trick Junie (of course, she can’t see it, because she’s under overwhelming amounts of stress, caused entirely by her inability to block a random Instagram account, a task so herculean she has to buy a timed safe to stop herself from checking her phone during the day. Oh, the stakes of modernity). In fact, most of the conflict in this book would have been resolved by Junie turning off her phone. It feels like horror for bored teenage girls.